MAXIMILIEN PELLET

[FR]

Maximilien Pellet est né à Paris en 1991 où il vit et travaille.

Diplômé de l’École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris en 2014, il s’illustre au salon Jeune Création en 2018, avant de participer à la Design Parade Toulon en 2019. Longtemps engagé dans la coordination de la Villa Belleville (ateliers & résidence), l’artiste développe depuis plusieurs années un travail d’envergure sur l’histoire des représentations et la notion de décor. Après sa dernière exposition personnelle à Paris en Mai 2022, Double V Gallery a présenté Maximilien Pellet en solo à ARCO Madrid en février 2023.

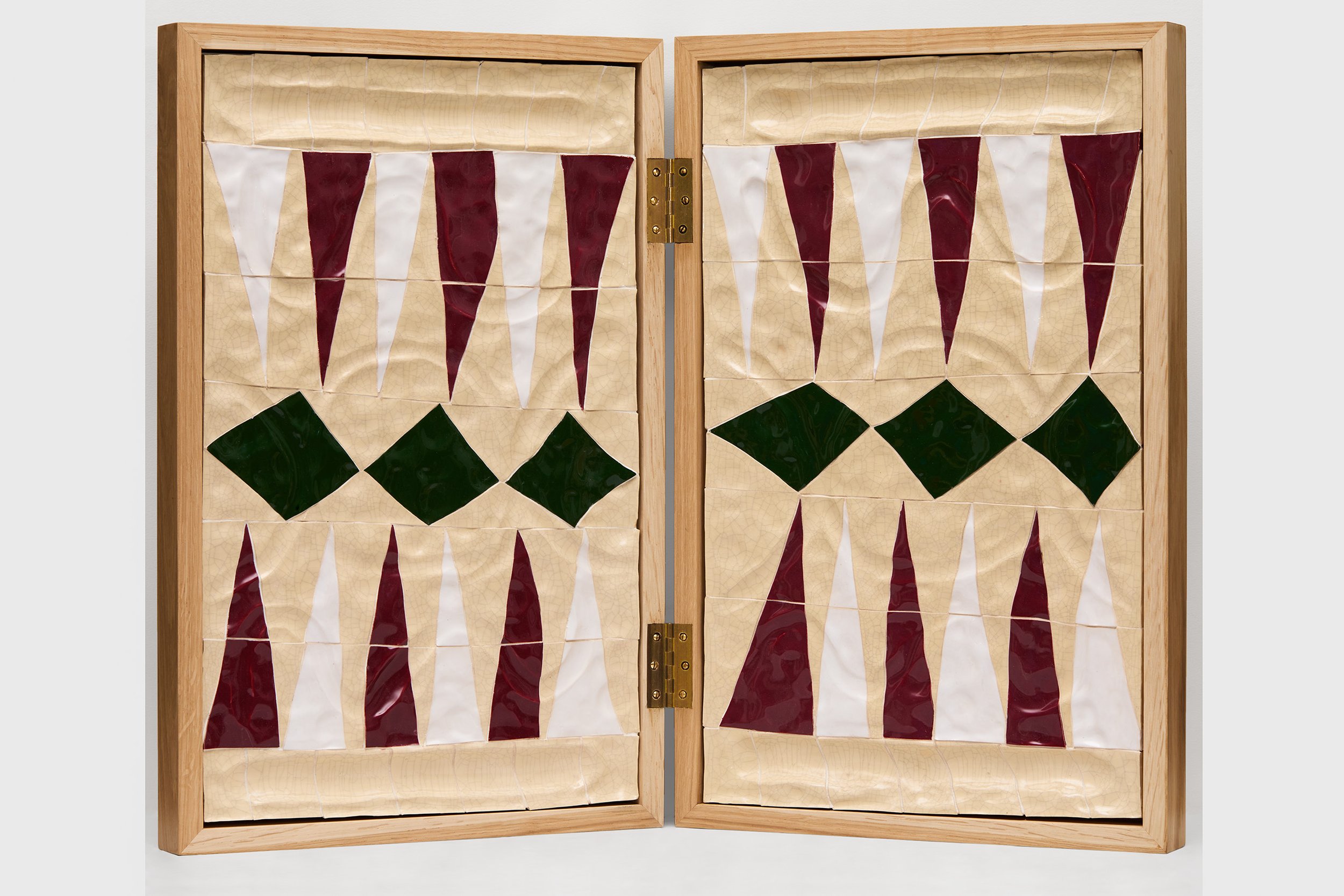

Maximilien Pellet aiguise une géométrie de la surface. Non pas que le plat soit la seule dimension de sa production, mais ses œuvres par leur qualité de paroi, leur logique de pavement et leur lexique héraldique, affichent un appétit flagrant pour la planéité.

Sa formation en image imprimée aux Arts Décoratifs de Paris, dont il sort diplômé en 2014, peut éclairer son aisance à composer des visions propres à la sérigraphie, à la gravure ou à l’édition. Il continue aujourd’hui à beaucoup dessiner, et toujours à penser par croquis, qui remplissent ses carnets.

C’est ensuite par son engagement successif au sein de trois ateliers associatifs incluant la villa Belleville où il est actuellement basé, qu’il acquiert des compétences au contact de complices et de nouveaux équipements. La mutualisation des outils assure une autonomie de facture. De la sorte, il perfectionne sa technique de l’enduit, puis de la céramique. Ces savoir-faire lui permettent d’affirmer un vocabulaire au fort potentiel combinatoire. Tout semble faire puzzle.

L’ensemble de son travail peut ainsi être lu selon le principe du tangram. Né d’un carreau de faïence qu’un empereur chinois aurait brisé, ce jeu est constitué de sept pièces élémentaires qui forment initialement un carré, mais dont la juxtaposition ouvre un panel infatigable de figures. D’un problème, résulte un éventail de solutions.

Outre l’inventivité plastique qu’elle éveille, cette parabole insiste sur l’économie de moyens et la ruse en présence dans la pratique de Maximilien Pellet. Après de premières expositions personnelles à Paris en 2017 puis Orléans et Pantin en 2019, la Double V Gallery lui consacre en 2020 une importante visibilité. Dans le sud de la France, Maximilien Pellet s’était déjà distingué dans le cadre du festival Design Parade organisé par la villa Noailles à Toulon. On pouvait y admirer un sol, dont les pavés bancals invitaient davantage à la contemplation qu’à l’usage. L’émail flashe d’une brillance électrique. Le répertoire relève du hiéroglyphe. Et sa passion du décoratif embrasse ostensiblement les joies du mural, et tout ce qui s’y accroche.

Joël Riff

Commissaire d’exposition La Verrière - Fondation Hermès & Moly-Sabata

[ENG]

Maximilien Pellet was born in Paris in 1991 where he continues to live and work.

He graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 2014, and made a name for himself at the Jeune Création salon in 2018 before participating in the Design Parade Toulon in 2019. Long involved in the coordination of the Villa Belleville (studios & residency), for the past several years the artist has been developing a large-scale work on the history of representations and the notion of decor. After his last solo exhibition in Paris in May 2022, Maximilien Pellet’s work was exhibited at ARCO Madrid in February 2023. Maximilien Pellet concocts and refines a geometry of the surface. The plane is not the only dimension of his creative production, but his works show a blatant appetite for flatness through their evocation of walls, their logic of pavement, and their lexicon of heraldry.

He graduated from the Arts Décoratifs in Paris school of art in 2014 with a specialty in the printed image, which sheds light upon the ease with which he composes visions specifically adapted to silk-screen printing, engraving, or manuscripts. He draws extensively and uses these sketches as an avenue for reflection, resulting in notebooks teeming with images. As a result of his involvement with three associative studios, including the Villa Belleville, where he is currently based, he discovered new equipment and acquired new expertise through collaborations with other artists. The sharing of tools offered liberation from the hegemony of expenses and he had the freedom to perfect his techniques, first in plasterwork and then in ceramics. These skills made him fluent in an expanded artistic vocabulary that was rich with cross-disciplinary potential.

Everything appears to be a puzzle. The entirety of his work can be interpreted using the principle of the tangram. Born from an earthenware tile that was broken into fragments by a Chinese emperor, this game consists of seven elementary pieces that initially form a square but can be reconfigured and juxtaposed to create an endless array of shapes. A simple problem that gives rise to a myriad of solutions. In addition to the conceptual ingenuity it awakens, this is also an allegory for the economy of resources and artful dexterity that are present in Maximilien Pellet’s approach. After solo exhibitions in Paris in 2017, then Orléans and Pantin in 2019, Maximilien Pellet had his work showcased at the Double V Gallery in 2020. The artist had already distinguished himself in the South of France at the Design Parade Toulon festival organized by the Villa Noailles. Among his most striking pieces was a precarious flooring more suited to contemplation than pedestrian use. The enamels flash with electric brilliance. The details conjure hieroglyphics. And, as always, his passion for decoration boldly embraces the joys of the mural and everything attached to it.

Joël Riff

Curator La Verrière - Hermès Foundation & Moly-Sabata

[FR]

Décorum

“ Aux murs, de grandes plaques de grès émaillé, certaines découpées comme des patrons de couture, d’autres, au format tableau, exhibent des compositions schématiques dans lesquelles de naïves figures, pareilles à celles qui ornent les vases étrusques où les parois des temples babyloniens, se mêlent à des motifs géométriques carnavalesques. Le trait est enfantin, joyeux ; la couleur, vibrante, est lumineuse. Sur l’une des œuvres de Maximilien Pellet, deux profils incisés à main levée braquent un œil écarquillé sur un trésor de pacotille. Ce même trésor s’entasse ailleurs dans un coin de la galerie Double V. On y trouve pêle-mêle des statuettes, des couronnes ou des clefs, et surtout ces montagnes de pièces, étincelants jetons de céramique jaune poussin, sans revers ni avers. Entre parade et jeux d’enfants, ici l’on joue, on fait semblant.

Diplômé de l’École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris en 2014, Maximilien Pellet s’est formé aux techniques de l’image imprimée (sérigraphie, gravure, édition), dont il garde le goût du motif clair, efficace, simple. Usant encore aujourd’hui du dessin comme d’une méthode de recherche et de préparation pour ses compositions, il s’est au fil du temps perfectionné dans les techniques de l’enduit, puis de la céramique, auxquelles il adapte son style hybride et syncrétique, certes profondément ornemental dans sa grammaire, mais non dénué de références à l’histoire des arts et des civilisations, depuis les artefacts archéologiques jusqu’aux avant-gardes du 20e siècle. Matisse n’est pas très loin, avec ses papiers découpés ; le Bauhaus non plus, dont Maximilien Pellet semble poursuivre, à sa manière, le programme de décloisonnement entre les beaux-arts et les arts qualifiés de mineurs. Devant certaines œuvres, on songe volontiers au design pop et minimaliste des années 1970 ; pour d’autres, il faudra remonter aux hiéroglyphes antiques d’une Mésopotamie fantasmée, ou bien aller voir du côté des productions vernaculaires purement décoratives et des traditions folkloriques.

Outre la diversité des inspirations et l’inventivité des combinaisons de registres, ce qui frappe en observant le travail de Maximilien Pellet, c’est son apparente économie de moyens. Au trait naïf et faussement spontané des motifs qu’il décline, il faut ajouter la simplicité des accords de couleur : le plus souvent, une teinte dominante — pour ce qui concerne le présent corpus, principalement le bleu et le vert — associée à un cerne et un fond neutres — noir ou blanc cassé. Surtout, il se dégage de ses œuvres une certaine familiarité, que l’on doit tout autant au choix des formes qu’à celui de matériaux bien connus, et depuis longtemps utilisés pour les objets du quotidien et les parements domestiques.

Ce n’est d’ailleurs pas pour rien si l’exposition prend pour titre “Décorum”, terme qui définit à la fois l’espace scénique où se déroule l’intrigue au théâtre, mais également l’ensemble des éléments utiles au déroulement des processions et des cérémonies. Ce sont là les pièces disparates d’une dévotion en devenir ou d’un rite déjà professé. « Chemisier Officiel », « Uniforme Oracle », « Armure Prestige », nous conviendrons que les costumes de Maximilien Pellet ne sauraient être endossés par personne, qu’ils ne sont qu’une image. Qu’importe, n’est-ce pas là le propre du spectacle et du jeu ? Que nous acceptions de suspendre notre incrédulité au profit d’un récit plus grand que la réalité ? Si l’artiste nous trompe, s’il raconte des histoires, c’est uniquement parce que nous avons faim de croire.”

Thibault Bissirier - The Steidz

[ENG]

Décorum

"On the walls, large slabs of glazed stoneware, some cut out like sewing patterns, others in picture format, display schematic compositions in which naïve figures, similar to those adorning Etruscan vases or the walls of Babylonian temples, mingle with carnivalesque geometric motifs. The line is childlike and joyful; the color is vibrant and luminous. In one of Maximilien Pellet's works, two freehand-incised profiles gaze wide-eyed at a junk treasure. This same treasure is piled up elsewhere in a corner of the Double V gallery. Statuettes, crowns, keys and, above all, these mountains of coins - glittering chick-yellow ceramic tokens with neither obverse nor reverse - can be found in a jumble. Somewhere between a parade and children's games, here we play and pretend.

A 2014 graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris, Maximilien Pellet trained in printed image techniques (screen printing, engraving, publishing), from which he retains a taste for clear, effective, simple motifs. Still using drawing as a method of research and preparation for his compositions, he has over time perfected the techniques of enduit, then ceramics, to which he adapts his hybrid and syncretic style, which is certainly profoundly ornamental in its grammar, but not devoid of references to the history of the arts and civilizations, from archaeological artifacts to the avant-gardes of the 20th century. Matisse is not far away, with his paper cut-outs; nor is the Bauhaus, whose program of decompartmentalization between the fine arts and the so-called minor arts Maximilien Pellet seems to be pursuing in his own way. Some of his works are reminiscent of the pop and minimalist design of the 1970s; others are reminiscent of the ancient hieroglyphs of a fantasized Mesopotamia, or of purely decorative vernacular productions and folk traditions.

In addition to the diversity of his inspirations and the inventiveness of his combinations of registers, Maximilien Pellet's work is striking for its apparent economy of means. In addition to the naïve, deceptively spontaneous lines of his motifs, there's the simplicity of his color schemes: most often, a dominant hue - in the case of the present corpus, mainly blue and green - combined with a neutral outline and background - black or off-white. Above all, his works exude a certain familiarity, due as much to the choice of form as to the use of familiar materials, long since employed for everyday objects and domestic facings.

It's not for nothing, in fact, that the exhibition is entitled "Decorum", a term that defines both the scenic space where the plot unfolds in the theater, and the set of elements used in processions and ceremonies. These are the disparate pieces of a devotion in the making, or a rite already professed. "Official Blouse", "Oracle Uniform", "Prestige Armor", we agree that Maximilien Pellet's costumes are not for anyone to wear, that they are only an image. Who cares, isn't that what spectacle and play are all about? That we agree to suspend our incredulity in favor of a narrative that's bigger than reality? If the artist deceives us, if he tells stories, it's only because we're hungry to believe."

Thibault Bissirier - The Steidz

Vue du stand NADA New York, 2024 - Double V Gallery @ Adam Reich

Vue du stand Art Paris, 2024 - Double V Gallery @ Grégory Copitet

[FR]

Parmi eux les Magiciens

« Aux murs, au sol, un ensemble de terres cuites émaillées s’étirent entre peinture et sculpture, autant d’éléments de décor, d’ornements fragmentés, de visages également, et parmi eux les magiciens. Mais avant les murs, avant les sols, il y avait les carnets de dessin, des feutres et quelques stylos...

Au cœur de cet environnement de couleurs, de ces formes aux abords résolument décoratifs, on peut être surpris d’entendre Maximilien Pellet parler de « grammaire », de « répertoire », de « lexique » et même d’« abécédaire ». C’est pourtant par là qu’il faudrait commencer.

Avant les murs, avant les sols, il y avait les carnets de dessin, des feutres et quelques stylos, et des centaines de références, figures puisées ici et là – ici dans les encyclopédies illustrées que Maximilien collectionne, là dans les relevés archéologiques et autres reliques d’un art oublié. Il y avait les images glanées, le dessin et peu à peu la construction d’un vocabulaire de formes, d’une grammaire visuelle qui par la répétition devient lexique ornemental. Le dessin devenu ornement se cherche, s’étend et s’accumule, se répète et s’épure, jusqu’à ce qu’intervienne le carreau, qui découpe l’image et la prédispose déjà à sa future fragmentation. Car l’image n’est pas destinée à rester sur les carnets : elle doit rejoindre les murs, et puis les sols. Pour cela, elle doit passer par la terre.

Du dessin, Maximilien Pellet extrait des motifs, et les inscrit dans la terre : de l’argile liquide qu’il coule et dans lequel il vient peindre, qu’il travaille à la main – la surface conserve tous les effets de matière – et découpe ensuite, en morceaux qu’il cuit, émaille et assemble à nouveau. Il y a quelque chose de la magie dans cette inscription d’une image dans l’argile, dans l’action du feu qui en vitrifiant la surface la rend inaltérable, quelque chose du rite aussi : peut-être sont-ils là, les magiciens.

Les motifs se transforme ensuite, en mobilier dans l’espace, en colonnades de tableaux, d’ornements de chapiteaux devenus architectures. Les formes s’y déclinent comme un répertoire, appellent à un décodage peut-être, conduisent – leur titre nous y invitent – à projeter une narration : Les Trois escargots, Hippocampe, Le mystérieux parchemin, le motif se décrypte pour évoquer des images, et des histoires.

Alors, au delà des formes qui écrivent dans l’espace un certain langage visuel, au delà de ces standards nés de la répétition qui peu à peu voient naître un style, les œuvres de Maximilien Pellet nous projettent dans un imaginaire décoratif riche, deviennent les personnages d’un monde inconnu, d’une civilisation anonyme que nous sommes invité·es à découvrir.

Cette civilisation se trouve au confluent de références anciennes et de réécritures contemporaines. Au départ, il y a pour Maximilien Pellet la découverte de l’art pariétal, notamment des grottes de Lascaux et de Chauvet, et ce rapport de la peinture à la paroi, avec tout ce qu’elle véhicule de sens. Il y a ensuite la rencontre avec les arts précolombiens, la céramique, les motifs. Ou encore avec les arts de la Mésopotamie antique, les murs babyloniens de céramique, qui dans nos imaginaires transforment les espaces en scènes de théâtre. Ces productions millénaires, il les approche souvent par le biais d’encyclopédies illustrées : les formes y passent au filtre du contemporain, des multiples styles du XXe siècle. Ces ponts entre les cultures et les représentations l’intéressent, qui créent des décalages et certaines tensions visuelles, qui subsistent à mesure qu’il intègre ces images dans son propre répertoire, et qu’il les transforme à nouveau.

Ceci étant dit, on pense évidemment à l’histoire de la modernité occidentale, à l’intérêt des artistes du début XXe pour les relevés de peinture pariétale, à l’influence de personnalités comme l’archéologue Leo Frobenius sur les artistes de Bauhaus, à la découverte souvent cannibale de formes d’art éloignées : en lisant les œuvres de Maximilien Pellet on croit reconnaître toutes ces formes, mais cela n’est pas tout à fait juste. En effet, si les artistes des avant- gardes européennes cherchent dans l’ancien une certaine origine de l’art, Maximilien Pellet s’intéresse quant à lui à la migration des formes, qui passent des grottes du Paléolithique aux toiles de Klee et Kandinsky, aux imageries populaires, aux arts décoratifs et à la pop culture, traversent les civilisations et se transforment. Il ne s’inscrit pas dans la même dynamique que l’avant-garde, il porte sur elle un regard critique – comme une prise de recule – et apporte à ces formes une nouvelle évolution en les intégrant à son travail.

Alors, tous ces personnages devenus ornements s’exposent, aux murs et aux sols, avec leurs vies et leurs histoires. Parmi eux nous déambulons, pas à pas les faisons voyager à nouveaux, par nos regards et nos paroles les rendons vivants, les mettons en mouvement : parmi eux nous déambulons, parmi eux les magiciens. »

Gregoire Prangé

Critique de Jeunes Critiques d’Art & Commissaire d’exposition au musée LaM

[ENG]

Among them the Magicians

« On the walls, across the floor, a set of glazed terracotta pieces extend into a realm between painting and sculpture, embodying elements of decoration, fragmented ornaments, faces too, and among them, the magicians. But before the walls, before the floors, there were sketchbooks, felt-tip markers, and a few pens...

Amid this environment of colours, of these forms with resolutely decorative appearances, one may be surprised to hear Maximilien Pellet evoke “grammar”, “repertoire”, “lexicon”, and even “alphabet book”. Yet this is where we should start.

Before the walls, before the floors, there were sketchbooks, felt-tip markers, and a few pens, and hundreds of references, figures reaped from here and there – here from the illustrated encyclopaedias that Maximilien collects, there from archaeological surveys and other relics of forgotten art. There were the gleaned images, the drawings, and, gradually, the creation of a vocabulary of forms, a visual grammar that, through repetition, becomes an ornamental lexicon. Once the drawing becomes ornamental, it seeks, expands, and accumulates, repeats and refines itself, until the moment of the tile intervenes, cutting the image and anticipating its future fragmentation. For the image is not destined to remain in the sketchbooks: it must reach the walls, and then the floors. And for that, it must pass through earth.

From the drawing, Maximilien Pellet extracts motifs and inscribes them in clay: liquid clay that he pours, works by hand, paints – the surface retains all the effects – and then cuts into pieces that he fires, glazes, and reassembles. There is something magical in this inscription of an image in clay, in the action of the fire that, by vitrifying the surface, makes it unalterable; there is something of a rite too: perhaps they are here, the magicians.

The motifs are then transformed into furnishings in space, into colonnades of paintings, ornaments for the capitals of columns, thus becoming architecture. The forms are arranged like a repertoire, one that perhaps calls for decoding, leading us – through their titles – into a narrative: Les Trois escargots [The Three Snails], Hippocampe [Seahorse], Le mystérieux parchemin [The Mysterious Parchment]... the motif is deciphered to evoke images and stories.

So, beyond the forms that etch a certain visual language in space, beyond the standards born from repetition that, bit by bit, gives rise to a style, Maximilien Pellet’s works project us into a rich decorative imagination and become the characters of an unknown world, of an anonymous civilization that we are invited to discover.

This civilisation is at the confluence of ancient references and contemporary rewritings. For Maximilien Pellet, the discovery of cave art – particularly the Lascaux and Chauvet caves, and the relationship between painting and the wall, with all the meaning it conveys – was the starting point. Then there was the encounter with pre-Columbian art, ceramics, and motifs. Or again with the art of ancient Mesopotamia, the Babylonian ceramic walls, which in our imagination transformed spaces into theatrical stages. He often approaches these thousand-year-old productions through illustrated encyclopaedias: the forms are filtered through the contemporary, through the multiple styles of the 20th century. He is interested in these bridges between cultures and representations, which create shifts and certain lingering visual tensions as he integrates the images into his own repertoire and transforms them once again.

This being said, one obviously recalls the history of Western modernity, the interest that early 20th century artists took in cave paintings, the influence of personalities such as the archaeologist Leo Frobenius on Bauhaus artists, the often-cannibalistic discovery of distant art forms: when interpreting Maximilien Pellet’s works, there is the belief that one recognizes all these forms, yet this is not entirely accurate. Indeed, if some artists of the European avant-garde seek a certain origin of art in the ancient world, Maximilien Pellet is interested in the migration of forms, as they go from the caves of the Palaeolithic to the paintings of Klee and Kandinsky, from popular imagery to the decorative arts and pop culture, crossing civilizations and transforming themselves. He does not follow the same dynamic as the avant-garde but examines it critically – as if taking a step back – and introduces a new evolution to these forms by integrating them into his work.

Then, all these characters become ornaments, displayed on walls and floors, with their lives and their stories. Among them, we wander, step by step, making them travel again, bringing them alive with our looks and our words, putting them into motion: among them, we wander, among them, the magicians. »

Gregoire Prangé

Art Writer Jeunes Critiques d’Art & Curator LaM Museum